By Tony Kaye, Senior Personal Finance Writer

Higher interest rates equal higher yields on some investments, but not all.

When the Federal Reserve Bank’s chairman, Jerome Powell, signalled last week that United States’ interest rates are likely to stay higher for longer, many income investors there would have breathed a collective sigh of relief.

There was likely to have been a similar reaction from Australian investors when the Reserve Bank announced after its May board meeting it was keeping its cash rate on hold at 4.35%.

It makes sense. After all, unlike borrowers who are struggling to pay off debts at elevated interest rate levels, investors seeking to generate income (particularly retirees not wanting to take on significant investment risk) understandably like higher rates.

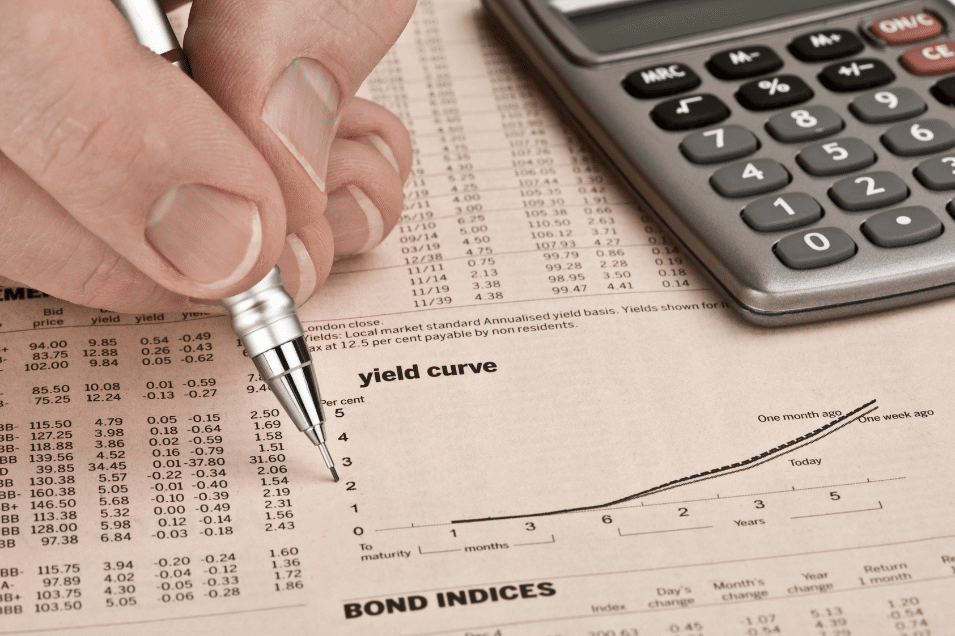

Higher rates equate to higher yields on certain types of investments. This has been the primary reason behind the large investor inflows into high-interest cash accounts and fixed-interest products such as bonds over the past two years ever since central banks around the world began ratcheting up rates to combat inflation.

Before then, central banks cut interest rates to record-low levels in order to offset the severe economic and business impacts caused by COVID-19 – a tactic that eroded the income returns of investors worldwide.

A quick glance at some of the current shorter-term interest returns on offer shows investors can readily park their money in fixed-interest investment products and receive yield returns in excess of 5% per annum.

Those yield returns reflect the expectation that official interest rates are unlikely to come down quickly, and when they do they will not fall back to record lows again.

Yields versus yields

Another major source of income for many investors are the dividends paid out by companies listed on the Australian share market and other markets.

During March, more than 80% of the largest companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) reporting their half- or full-year financial results to 31 December 2023 declared a dividend per share to their shareholders.

The total dividend haul amounted to around $30 billion, and the latest dividend payouts have been steadily trickling through to investors over recent weeks.

Understandably, many income investors are attracted to companies with a long track record of paying out dividends to their shareholders.

Another key attraction for investors is Australia’s dividend imputation regime. Introduced in 1987 with the objective to prevent double taxation of dividend income, franking credits apply to the tax paid on earnings generated from the domestic activities of Australian companies.

The distribution of franking credits reduces the applicable tax rate on dividend income to that of the end investor. For investors with a lower tax rate than the corporate rate, a cash refund is received.

So, in searching for higher dividend income returns, some investors may focus on a company’s dividend yield.

A scan of companies on the ASX shows some have dividend yields well in excess of 10%. They include some well-known companies paying fully franked dividends – that is, their investors get a 100% tax-paid franking credit.

A dividend yield is calculated by dividing a company’s prevailing share price by its declared annual dividend payment per share. For example, a company with a share price of $5.00 paying an annual dividend of 50 cents per share has a dividend yield of 10%.

But here’s where it’s very important to understand the difference between the yields payable on cash and fixed-interest products versus dividend yields.

Investors in most cash and fixed-interest products generally expect to receive a fixed interest rate return based on their current investment balance. Account rates do change, but not frequently.

Dividend yields are very different, because they change whenever a company’s share price changes. They rise whenever a company’s share price falls, or fall whenever a company’s share price rises.

Using the hypothetical company example above, if that company’s share price fell over time to $4.00, its dividend yield (based on its annual dividend of 50 cents per share) would have risen to 12.5%.

That is the case with a number of the ASX companies currently showing the highest dividend yields. Their share prices have fallen quite sharply over the last year, some by 30-50%.

And another factor to consider is that dividend payouts by companies are not necessarily set in stone. Companies – especially those that have experienced sharp share price falls – may decide to halt their dividend payouts.

There have been many instances in the not too distant past when some of the largest listed Australian companies, including the major banks and resources companies, have either cut or deferred their dividend distributions.

Franking credits can also be cut at a company’s discretion, based on its earnings results.

How to reduce dividend payout risk

The easiest way to reduce dividend income risk – the risk of being over-exposed to the payout policies of specific companies – is through diversification.

The best way to achieve that is by having broader exposures to diversified income streams via a large pool of listed companies, such as though managed funds or exchange traded funds (ETFs) that cover a wide range companies in a single market or across multiple markets.

Think of funds as a form of fishing net that will catch the dividends of every company that falls into their investment focus.

For example, the Vanguard Australian Shares Index ETF (VAS) – which is the largest ETF listed on the ASX by market capitalisation – tracks the S&P/ASX 300 Index by investing in Australia’s top 300 companies. Many of the largest companies pay out interim and final dividends based on their earnings reporting cycle.

The key advantage for investors is that irrespective of individual company dividend yields and payouts, a fund will aggregate all dividends and distribute them to investors.

While dividend flows may decline at different times, having exposure to many companies allows investors to capture a greater amount of the total dividends spectrum.

Doing this also eliminates the need to focus on the dividends of individual companies and their dividend yields, which can be a potential trap for investors.

Important information and general advice warning

An investment in the Vanguard Australian Shares Index ETF (VAS) is subject to investment and other known and unknown risks, some of which are beyond the control of Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd, including possible delays in repayment and loss of income and principal invested. Please see the risks section of the Product Disclosure Statement (“PDS”) for the VAS for further details. Neither Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd (ABN 72 072 881 086 AFSL 227263) nor its related entities, directors or officers give any guarantee as to the success of the VAS, amount or timing of distributions, capital growth or taxation consequences of investing in the VAS.

© 2024 Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd. All rights reserved.